I have about six books on adoption—memoirs and monographs—in various states of unreadness. That is entirely typical. I would like to add a seventh: Florence Fisher’s The Search for Anna Fisher, about her quest to find her birth mother. Florence Fisher died last year: October 1, 2023. Marley Greiner, a cofounder of Bastard Nation, eulogized her, while offering some characteristically sharp observations, here.

Fisher was one of the foremost pioneers in adoptee-rights activism. Before almost anyone else, she identified adoption as a rights crisis for adoptees. For instance, she wrote:

Sealing our records is a violation of the Constitution. We are told the law is protecting the privacy of our natural parents. My mother has the right to privacy from you, but not from me, her baby. She has no right to privacy at the expense of my anonymity.

I echo this regularly when I say that privacy entitles you to withhold from me facts about you, not facts about me. My identity is not something anyone else can claim as theirs.

I would give you the citation for this passage, but it turns out to be difficult to find any copies of Florence Fisher’s book. There are no copies in my regional library network. It is long out of print. Used copies of the mass-market paperback start at $40 online. It’s available at the Internet Archive for checkout by the hour—feasible, but a little annoying. Luckily, I can get a copy through my statewide interlibrary loan consortium. While I wait, I will get a few of my other books-in-progress out of the stack.

I spent the first week of April in the company of adoptees. I have been talking about adoption on social media for about five years, and two years ago, as people began to notice me, I received invitations to appear on adoptee-focused podcasts: Bryan Elliott’s Living in Adoptionland, Sarah Reinhardt and Louise Browne’s Adoption: The Making of Me, and Haley Radke’s Adoptees On. I was even invited to Zoom in on a meeting of a bioethics class taught by a philosophy professor who is a “known” (that is, non-anonymous) gamete donor. But I did not begin to meet my online connections in person until this year—with the exception of Megan Galbraith, author of the brilliant and wondrously unsettling “adopted child’s memory book,” The Guild of the Infant Saviour. Megan lives not far from the western border of my small state of Massachusetts. A few summers ago my spouse and I met her at Mass MoCA in North Adams, an enchanting place, a onetime factory complex of huge, spacious brick buildings perfect for hosting large-scale exhibits. That was the first time in my life that I had ever talked about adoption with another adopted person, and what a talk it was. Megan not only understood my perspective but had thought for so long and so deeply about adoption that I had the privilege of sitting with her and imbibing the wisdom she freely shared.

The next time I socialized with adoptees was at a reception for an event in New York City during the first week of February: Operation Fog Lift NYC. I was unable to stay for the weekend, but at a midtown Manhattan restaurant on Friday night I met a number of my social-media connections, including the podcasters Sarah and Louise, and Gregory Luce of Adoptee Rights Law Center. A brief but thrilling moment: a roomful of people brought together by the desire to find community in the profoundly isolating experience of being adopted.

In late February, wearing a cast boot to protect the foot I had broken a week earlier, I shuffled into Brookline Booksmith to see sociologist Gretchen Sisson speak with journalist Rebecca Traister about Gretchen’s new book Relinquished, which I’ve discussed before (and will again). There I met an adoptee I’d only known by her online pseudonym, like several I’d seen a few weeks earlier in New York. Gretchen discreetly invited me to join her with Rebecca and a few others for post-talk socializing at a local restaurant, one door over from the office of my therapist, who for more than six years has patiently and skillfully helped me to orient my experiences as an adoptee within my overall self-narrative.

And then the events of April. On the afternoon of April 4 I took a commuter-train ride from Boston to Providence. I walked to a coffee shop and sat at a booth with the scientist, writer (poet, memoirist, editor), environmental activist, and fellow cancer survivor and adoptee Sandra Steingraber. We were both registered attendees of the 2024 conference of the Alliance for the Study of Adoption and Culture at Brown University—three days of talks and meals with adopted people who are producing scholarship and art about adoption. Sandra was my conference partner and my houseguest. On our daily rail journeys back and forth I enjoyed a sense of easy friendship with this extraordinarily accomplished and endlessly creative, energetic woman. My goal at the conference, superabundantly achieved, was to listen, learn, and make new friends. In late 2023 Susan Kiyo Ito, author of the recently published memoir I Would Meet You Anywhere (a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist), told me that she would be doing a spring book tour and was looking to hold an event at a public library in the Boston area; would I be interested in organizing one at my library? With my assistant director’s enthusiastic approval, we made arrangements for an author talk, in the form of a conversation between the two of us. We scheduled it for April 8. In Providence on April 4, Sandra and I met Susan, at last. It felt like three old friends back together, an illusion I’ll cherish, and one not too unlike the illusion of ancient connection I felt when meeting my birth mother’s family.

Friday the 5th was my 50th birthday, and I was spending it with dozens of adopted people. Word had gotten round that I and another adoptee (and conference presenter) Susan Harris O’Connor shared the birthday. And people gave me gifts: Sandra had brought to my house tea, chocolate, and local salt; Susan gave me salt too, and an origami crane, and a copy of an anthology she had coedited of essays and poems by adoptees; Boston-based counselor, lecturer, and eminent adoptee advocate Joyce Maguire Pavao gave me a slender journaling notebook. Alice Diver, Lecturer in Law at Queen’s University Belfast, gave me a copy of her recently published scholarly monograph Genetic Stigma in Law and Literature.

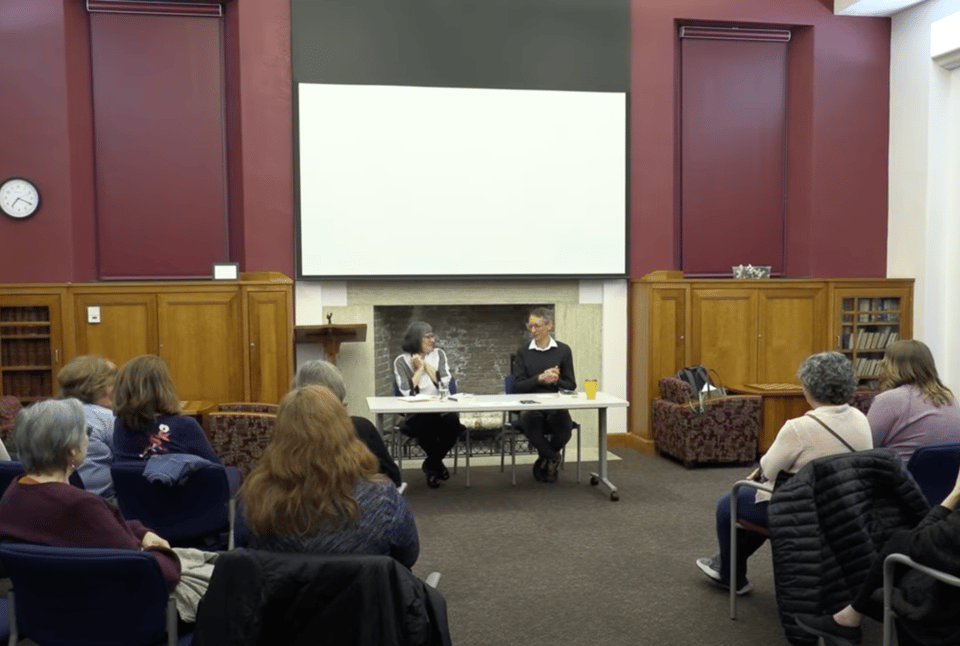

Sandra remained in town through Monday, the day of Susan’s event at my library. She sat next to my spouse, with a longtime friend of mine behind them, as Susan and I talked and then took questions from the audience. The town’s public-access cable channel recorded the whole thing, and it’s viewable here. Joyce Maguire Pavao was there, along with several people I had

Three weeks on and I’m not sure I’m fully sensible yet of everything that happened over those five days. I have been thinking about what adoptees can give each other through fellowship. Parasocial relationships are not intimate, and I have learned how perilous it is to forget this. It is no substitute for the invitation to trust and openness (and open-endedness) that arises from time spent in person.

What do I seek from fellowship with adoptees? For the past ten years, since I found my birth mother, I have embraced my adoption as the center of my identity. I examine everything about myself—the incidents and episodes of my life, my values and commitments, my kinship and friendship relations, my strengths and my flaws—through my adoption. One risk, perhaps, is navel-gazing, as Werner Herzog warned about the work of self-excavation in memoir:

It is not healthy if you circle too much around your own navel. And it is not good to recall all the traumata of your childhood. It's good to forget them. It's good to bury them. Not in all cases, but in most cases. So psychoanalysis is doing that. I do not deny that it is good and necessary in a very few cases. Yes, I admit it, but it's not my thing.

But if I had not embraced community with other adoptees, I would not have heard Susan Ito’s brilliant retort: “Well, that’s fine for you to say, if you know who your navel was attached to.”

To find community with adoptees is to embrace, collectively, adoption as an identity. This might seem paradoxical, because adoption isolates. Our predicament as adoptees is that it is up to us to define for ourselves a basic element of identity: our kinship relations. We also seek to stitch together our histories from disparate elements that were never meant to be connected, by any one person, into a whole. We are constructing ourselves at the same time as we are exhuming our pasts. That is lonely work, and to find community in that work can help to save us from a deadening sense of pointlessness.

Now, three weeks since all these events, since I spent time in rooms full of adoptees, and in intimate conversation with adoptees, my birthday balloons are still floating in my dining room. They’ll stay there until they sink back to earth.

You just read issue #54 of This Is Not A Legal Record. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.