This post is dedicated to my Aunt Marianne, the only person I know of in my family who has read Derrida.

Last week, from April 4 to 6, I attended the conference of the Alliance for the Study of Adoption and Culture (ASAC), held this time at Brown University, a train ride away (well, two train rides away) from my home near Boston. I left academia thirteen years ago, but I was thrilled to be among scholars and writers and artists, ages spanning at least five decades, who are creating knowledge and art about adoption. And I was delighted to be free of the pressures of "performance," not being a presenter, but only an attendee, there to learn from others and to make friends. I did a lot of both.

Word had gotten out that the 5th was my birthday. My 50th, in fact: right on time, my "Hello, we are the AARP" letter was delivered just a few days earlier. I bonded with the adoptee author, social worker, and activist Susan Harris O'Connor over our shared birthdate. Other participants approached me with gifts. I got a tiny journal, two jars of flavored salt, chocolate and cheese--and books. Brilliant books by adoptee scholars and writers.

It was bittersweet to have no institutional affiliation. I don't often look back regretfully on having ended my long and tortured romance with academic life, but this was a moment when I felt the loss. As much as I admired the scholars presenting their work, I also felt the gentle sting of envy.

But what work! I attended a session involving two early-career scholars, both at schools in the Boston area, both adopted--one from Korea, the other from Vietnam. They were presenting work touching on questions of adoption and narrative: how adoptees make meaning out of the scraps and fragments and relics of the histories from which our adoptions are designed to sever us. Being literary theorists, they were less afraid than I would have been, having been trained in (primarily) Anglophone academic philosophy, to invoke the work of Jacques Derrida. One of them talked about Derrida's notion of the "Archive Fever," which--if I see it rightly--is about both the drive to institutionalize memory with official documentation, recordkeeping, notes and files and photos and all the other material we can box away, and about the drive to return to the archive, again and again, to consult and interrogate the official record.

Now I'll do something I have never done before: quote Derrida himself (in translation).

And the theory of the archive is a theory of this institutionalization, that is to say of the law, of the right which authorizes it. This right imposes or supposes a bundle of limits which all have a history, a deconstructible history, and to the deconstruction of which psychoanalysis has not been foreign, to say the least. In what concerns family or state law, the relations between the secret and the non-secret, or, and this is not the same thing, between the private and the public, in what concerns property or access rights, publication or reproduction rights, in what concerns classification and ordering (what comes under theory or under private correspondence, for example? what comes under system? under biography or autobiography? under personal and intellectual anamnesis? in so-called theoretical works, what is worthy of this name and what is not?

An adoptee will catch a lot in here to pique their interest if that adoptee, like me, has caught the Mal D'Archive, the Archive Fever.

By this I mean both recording for the archive, and retrieving from it. This newsletter is part of my effort to "institutionalize" my thoughts and feelings about my adoption, and about adoption itself. The activity of forming those thoughts and feelings into publicly accessible data for the archive is a way I choose to make my identity as an adoptee concrete, visible, and real.

But on the side of retrieval: what fascinated me in the talk at ASAC that invoked Derrida's notion of the Archive Fever is that I feel the impulse, really a compulsion, to gather every last scrap from the scattered, everywhere-and-nowhere "archive" of my pre-adoptive life and early life as an adopted baby.

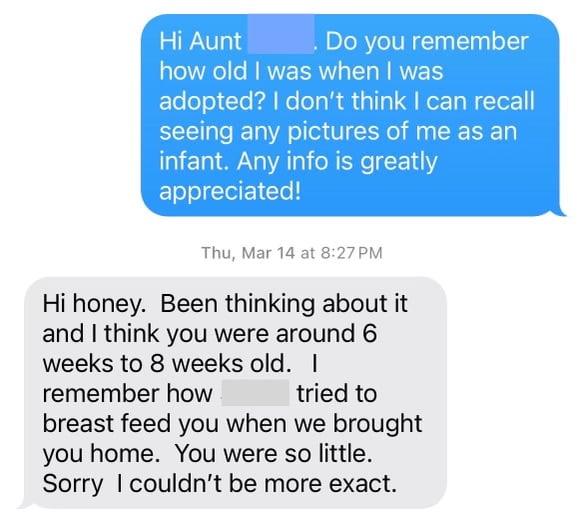

Baby photos: not in the Archive. My aunt's memory: now in the Archive as a fragment of a text exchange in my camera roll, and embedded in this newsletter post. I did not ask for information about my adoptive mother's attempt to breastfeed me, but I can't un-know it now; into the Archive it goes, for good or ill. Both.

I think about the Archive constantly. How does the Archive mark me as official, "real," and how does it invalidate and erase me? And my adoptive parents, and my birth mother, and my biological father? The vital record produced at the time of my birth, recording the actual facts, naming my birth mother, and my weight, and the attending physician, and my birth mother's residence, and showing her handwriting at age 22, loopy, not sharp and angular as it became: all of it stamped "THIS IS NOT A LEGAL RECORD." In the Archive of the State of Alabama as a document of truth demoted to legal unreality; in my Archive as the same, but so much richer for me. Derrida talks about how the Archive marks the boundaries between private and public, secret and non-secret. The secrecy of the Archive is a taunt and a torment to some adoptees. If people who oppose unsealing birth records invoke the specter of the "unhinged adoptee," they are not wrong. Who could know that one bit of writing in one file in the Archive--a woman's name in her own handwriting--would send me to my computer to find my original family, would ignite the Mal D'Archive in me, an obsession that by its nature can never be satisfied?

The Mal D'Archive is not "reasonable." I want "everything," and the hunger for "everything" not only steamrolls the "private/public" boundary but looks, to outsiders, like a mania. I want every last scrap of material Catholic Social Services has kept about my adoption. I want to know not only what is in those files, but everything about how those files were generated. Who were the agency workers who selected the people I was to learn to call "Mom" and "Dad?" Was there a shortlist of potential adopters? Who was on the shortlist? I want to trace out every nearly-missed past I could have had. There is something "sick" about this--as if one wanted to be able to crawl back into one's mother's uterus and relive the experience of being there.

The hunger is unsatisfiable in two ways. First, I will never get those files from Catholic Social Services. The watchword of the Church and all its activities is Secrecy. Second, there is no limit to what else I could want to know. The drive to have "all the facts," an ill-defined end, is compulsive and can meet only with cessation, never satisfaction.

Derrida compares the Mal D'Archive to the Freudian concept of thanatos, the Death Drive:

As the death drive is also, according to the words Freud himself most stressed, an aggression and a destruction drive, it incites not only forgetfulness, amnesia, the annihilation of memory, as mnemé or anamnesis, but also the radical effacement of that which can never be reduced to mnemé or to anamnesis ...

Here I have to acknowledge the fact that my Archive Fever is in part an expression of aggression--even of vengeance. In building my Archive I am building my identity. In building it out of materials not originally intended for me, I am creating an identity in defiance of, even as revenge against, the policies and institutions and dogmas and ideologies designed to tell adopted people who their adoptions make them into. I court incomprehension and disapproval everywhere. My ex-spouse's disapproving reference to my "instant family" I claimed as my own after meeting my biological relatives; my adoptive father's stung reaction to hearing me refer to my birth mother as "my mom;" strangers online who presume to inform me of everything good about adoption I allegedly ignore in criticizing it (also part of creating my new identity).

I do not think there is any way to justify or rationalize the transformative effects of the Archive Fever. I think many other adoptees understand it, have felt its grip. I am sure many others never will. Some of them vehemently reject the Archive. They are very happy, thank you, very "secure in who they are," and have less than no desire to visit the Archive. This is an act of identity formation too. I might call them unreasonable, but turnabout is fair play.

The filmmaker and writer Werner Herzog published a memoir last year: Every Man for Himself and God Against All. Promoting the book, he repeatedly warned against introspection that goes too deep. He compared deep self-excavation of one's past to flooding a room with light that fills every corner and niche, rendering it uninhabitable. On the NPR program Fresh Air he said this:

It is not healthy if you circle too much around your own navel. And it is not good to recall all the trauma of your childhood. It's good to forget them. It's good to bury them. Not in all cases, but in most cases. So psychoanalysis is doing that. I do not deny that it is good and necessary in a very few cases. Yes, I admit it, but it's not my thing.

I hosted an author talk at the library where I work, and my guest was Susan Ito, who recently published her adoption memoir I Would Meet You Anywhere. I asked her about Herzog's remark, and she said something I will not forget. To paraphrase: It is easier to reject navel gazing when you know who your own navel was attached to. Hunger is neither reasonable nor unreasonable, perhaps; but we were starved.

You just read issue #53 of This Is Not A Legal Record. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.