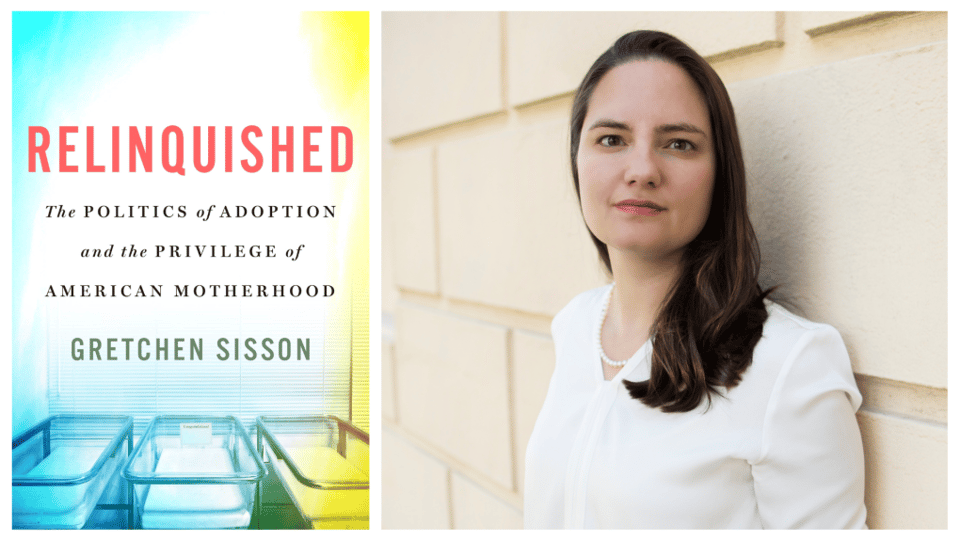

Last week I attended a bookstore event at which Gretchen Sisson discussed her new book Relinquished: The Politics of Adoption and the Privilege of American Motherhood. Sisson is a qualitative sociologist at Advancing New Standards In Reproductive Health (ANSIRH), part of the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. Relinquished, like Ann Fessler's The Girls Who Went Away and Rickie Solinger's Beggars and Choosers, directly confronts the effects of adoption, as a set of legal, economic, and social practices, upon pregnant people who lack the resources and support they need for parenthood. Whereas Fessler's book compiles oral histories of birth mothers from the Baby Scoop period (1945-1974), Sisson foregrounds birth mothers from the first two decades of the 21st century, combining their stories, in their own words, with analysis of the social context in which they relinquished their children for adoption--or as I often prefer to say, lost their children to adoption.

I met Gretchen over coffee in San Francisco in August of 2023, as the galleys were being prepared for publication. (Note: when I refer to her as a personal acquaintance, I will use "Gretchen." When I refer to her as a scholar and researcher, I will use "Sisson.") She shared a PDF of the galleys with me, but as I sheepishly explained to her last week, I had not read them. Oddly (and irrationally), I felt it was an illicit privilege to read the book in advance of publication, even though I had preordered a copy months earlier. I believe I was a bit overawed. Both then and at the book talk, I felt some shock that this person, who had begun to take an interest in adoption policy, practice, and politics while working with teenage mothers during her years as a graduate student in metropolitan Boston, had, without any direct experience of adoption as part of the so-called "triad" (adoptee, birth parent, adoptive parent), recognized the inequity and exploitation on which the private adoption industry rests and had decided to study it systematically.

I mentioned to Gretchen that Relinquished is an excellent title, but that it also pricked my ears as an adoptee. Because as a verbal adjective, the word describes not the women whose stories she relates, but people like me: adoptees. We are the relinquished. In another sense, relinquishing parents are themselves relinquished: relegated, marginalized, generally voiceless in the joyful clamor that attends every new adoption. Gretchen acknowledged all this, but she noted (as she does in the book) that it is adopted and displaced people who have led movements for abolishing adoption as it is currently practiced, and whose voices have helped to guide her work. The book's aim is to present the authentic voices of parents who have lost their children to adoption. In that sense it is not "about" adoptees. But because it illuminates their experiences--the experiences of adopted people's parents, parents like my own birth mother--and because its arguments are a crucial part of the case for reform and abolition of adoption, I regard this book as a landmark in the history of research on adoption, and one of the most valuable scholarly contributions to the struggle for adoptee justice in the entire history of that struggle.

The next several newsletters--with an interruption or two--will constitute an extended review of, and meditation upon, Relinquished. I had supposed I understood what adoptee and birthparent advocates meant by calling the private adoption industry "predatory"--or indeed, why to call it an "industry" at all. But Sisson sets out the facts that compel these descriptions. The appalling truth, in short, is that adoption agencies chase pregnant people in crisis; those people do not chase the agencies.

Sisson (pp. 63-64):

Most women seeking abortion are fundamentally uninterested in adoption. In a survey of over 5,000 abortion patients, they were asked a series of true/false questions including "I want to put the baby up for adoption instead of an abortion." In response, 99 percent of participants said that was "false," and exactly 0 percent said it was "true" (1 percent said "kind of"). Adoption was often ruled out--if it was considered at all--because women simply felt it was not right for them, either because they had health reasons for not wanting to continue their pregnancies, or because they felt there were already too many children in need of homes. Another study of interviews with seventy women who'd recently had abortions found that none of them seriously considered adoption, mostly because they believed it would be too emotionally traumatic. These feelings about adoption were equally held by focus groups of both "pro-choice" and "anti-abortion" women, all of whom considered adoption to be emotionally painful not just for mothers, but for the children who would be relinquished. In another study examining the decision-making of women who'd had an abortion, most of them were unequivocal in ruling out adoption, with one participant alluding to the flawed reasoning of anti-abortion advocates:

I don't want to give my child away to nobody, and I'm not ... and that's the part they don't understand. I can't just be bearing a child for 9 months, going through the sickness and then giving my child [away]. I can't.

More surprising, at least to people who perhaps had not heard the voices of women who had lost children to adoption, was the finding of the Turnaway Study, headed by demographer Diana Greene Foster, that even women denied abortions for medical reasons or because of the progress of their pregnancies overwhelmingly rejected placing their children for adoption. Michelle, a participant in the study, said this (Relinquished, p. 64):

There's no way that I would be able to carry a baby that long and then give it away knowing that I have two other children at home and then have that kid maybe come back one day and say, "Why didn't you want to take care of me?" I couldn't do it.

25 percent of the women participating in the Turnaway Study who were denied abortions reported considering adoption. 9 percent relinquished. Elsewhere, Sisson notes that this percentage corresponds almost exactly with that of the (mostly white) unmarried pregnant women of the Baby Scoop period who relinquished their newborns: only about 9 percent of those unplanned pregnancies resulted in relinquishments. (The overall number of relinquishments was much higher, of course, owing to the inaccessibility of abortion to these women in the years before Roe.) Despite all the cultural dogmas about the "bravery" and "selflessness" of relinquishing a child for adoption, despite the strenuous arguments made by social workers 60 years ago and agency PR teams now about the great boon conferred upon a child by sending it to a "stable, prosperous, loving home," relinquishment was and is deeply unpopular. I would hazard that when these women speak of the trauma they expected it to inflict upon themselves, and upon the children they surrendered, they speak less with far-seeing wisdom than with a common sense that anyone not discussing the "social good" of adoption would readily summon.

We might expect a social world that respects the autonomy of women, and that acknowledges the deep unpopularity of adoption as a remedy for unplanned pregnancies, deep even among those who know that their life circumstances make parenting all but impossible, would find ways to make parenting tenable, rather than to try to persuade women in difficult circumstances to make the choice that they generally abhor. But that is not our social world in the United States. Ours is a world in which political leaders from both parties express a commitment to

promoting adoption, to "streamlining" adoption, to incentivizing adoption. And while much of this posturing concerns adoption out of foster care--a subject studied in work on the "family regulation" or "family policing" system in the US--it remains true that Democrats and Republicans eagerly cite the promotion of adoption in all forms as an area of bipartisan consensus and cooperation.

Our social world involves greater acceptance of single parenthood--at least for less marginalized groups. It is also the era of "open" adoptions, in which (people enjoy telling me) adoption is "different from when you were born." In this world, promotion of adoption means chasing pregnant people, luring them, seducing them. Adoption agencies and hopeful adoptive parents have become entrepreneurial; they hustle for birthparents. Sisson explains how agencies and parents use the techniques of search engine optimization to ensure that a wide range of phrases a person with an unplanned pregnancy might Google will call forth ads promoting relinquishment for adoption. The range is remarkable: from "assistance for pregnant mothers in Nevada" to "unplanned baby announcement" to "I'm scared I'm pregnant I'm fifteen." A service called Adoptimist sells hopeful adoptive parents tools to "instantly expand your adoption outreach," with "highly targeted Google banner ads" and promotion on social media. In Massachusetts, a scandal erupted when Boston-based Copley Advertising was discovered to have offered "geofencing" services to place ads on the phones of anyone within a certain range of an abortion clinic; Bethany Christian Services, an adoption agency, was one of its clients.

Sisson describes the powerful effects these techniques can have on vulnerable pregnant women. Presented with profiles of well-off, kindly-seeming professionals heartbreakingly speaking of their wishes for a child to make their lives whole ("Dear birthmother, we've been waiting so long"), many of the women Sisson interviewed spoke of feeling compassion for these hopeful parents, wanting to do what they could to make their agonizingly deferred dreams come true. Pregnant women, with little to no resources or support to keep the children they wanted to keep: feeling compassion for these affluent professionals. It's a psyop, and sometimes it works.

As I was reading, I mentioned to an acquaintance what I was learning about these advertising techniques. They replied, "Yes, but don't most all businesses use these techniques?" I think they meant that what the agencies and parents are doing is no more coercive than is advertising generally. But the reply proved the point. These agencies are businesses. They constitute an industry. Their product is babies. And they are fishing for producers of that product. The technique is not coercive, but it can be compelling when targeted at the right person at the right vulnerable moment, inclining them to a permanent, life-altering, generationally repercussive decision they might not have made had other counsel been available. Online, that counsel is silenced in the clamor of the adoption hustle.

You just read issue #51 of This Is Not A Legal Record. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.